A Modest Proposal for CBS’s “Kid Nation”

Here’s a modest proposal: as soon as our little tykes are weaned, let’s put them in the desert with a bunch of bigger kids and see if anyone, say, drinks bleach on accident. Or dies. Won’t that be amusing? Maybe the kids will gang up into warring factions in a struggle for dominance and kill each other! Won’t that be neat? And if we put it on prime time TV we can all watch!

I really, really wanted to pitch this idea to CBS. I thought it would make an excellent reality TV show. I’m such a fan of TV that I can live happily without one, but I have an entrepreneurial streak a mile wide and after I saw my son reading Lord of the Flies a couple of weeks ago I thought to myself, “Hey! What an idea!”

I got all dressed up in my best lawyer outfit, high heels and makeup and perfectly coiffed hair and all, and grabbed the morning paper as I headed out the door, ready to make a few calls and set up a time to meet with the network executives. I just knew they’d clamor for me to hurry on over with my idea.

My contacts aren’t the bifocal type so I had to wait until I got to the office and found my reading glasses before I could peruse the morning tabloids, though. Once I perched them on the tip of my nose, there it was, to my bleak dismay. Over a half-eaten croissant and a cup of cooling Starbuck’s (a candy bar in a cup is still a candy bar), I saw that my brilliant idea had not only been stolen by some Hollywood thought-thief, but that CBS had already filmed my idea! Kid Nation was already in the can and had attracted its first threatened lawsuit!

There is still hope for me. Suit has not yet been filed. Bereft of my opportunity for reality show fame, I’m sure I can muster the necessary outrage for filing suit on behalf of these kids. I have represented kids for almost 20 years, after all – what’s one more suit on their behalf? And this one will give me great pleasure, because not only will it be against the tormentors of my clients, it will be against the people who publicly and obviously disregarded their best interests.

Did you get that line? “Publicly and obviously disregarded their best interests” – wow, I’m in lawyer mode! Hmmm… what other equally spurious arguments can I come up with to bring this case to dubious justice? Oh! I know! I’ll demand that the press help me investigate how CBS could manage to get the parents of 40 kids between the ages of 8 and 15 to agree to send them to a ghost town for nearly six weeks during the school year with no adult supervision and no classes! I’ll file documents requesting information on how much the children (or their families) were paid for the kids’ participation in this show ($5,000.00 is the figure CBS claims), and then I’ll demand to see documents showing how New Mexico’s and the federal government’s child labor laws were complied with, what with no adults to take care of these kids.

Man, I’m on a roll now! I can hear CBS crying foul in my mind’s ear. I’m just another money-grubbing lawyer trying to get a huge settlement out of the deep pockets of the TV network.

Those eight year olds knew what they were getting into, the corporate lawyers will insist. It will be very hard to refute, because we all know what brilliant negotiators fourth-graders are. “Because I said so” just won’t work with all of them, you know.

When I point out that only one of the kids was 15, and that a dozen of them were aged 10 and under, I’m sure the network will flick away my objections with a disinterested wave of its manicured hand. Younger children probably won’t be as mean as the ones in that famous book by Sir William Golding. In fact, I’m sure that recent news reports that kids aged seven to nine maliciously killed a six year old were grossly exaggerated. After all, those kids were in Canada, were not on a reality TV show, and had not been promised prizes like iPods for their participation.

CBS is likely to claim that there were tons of adults around all the time, and that like on any reality TV show they were quick to get the bleach-drinking kids medical attention. That won’t daunt me in the least, though, because I’ll claim that had those kids been properly supervised they wouldn’t have been drinking bleach in the first place. And when they argue that the 11 year old whose face was burned by cooking grease was doing the same thing 11 year olds do at home every day, I’ll taunt them with “Yeah, well, those 11 year olds are cooking with grease under adult supervision!”

It won’t endear me to the network, but maybe I can win another non-meritorious lawsuit and win a pile of money doing it. I need to maintain the pseudo-integrity of my profession, after all.

And maybe as an extra added bonus I can get some parents to wake up and realize that unsupervised preteens can get seriously hurt, and even (gasp) die if their parents don’t protect them.

Defeat in Iraq?

The following is a story off the wires from a news service in India. Upon reading it, my question is this:

If the American Intelligence community believes that the British have been defeated in Basra (Al Basrah on the map above), what must they think has happened in Baghdad, where violence is so much worse? And why isn’t THAT being reported?

London, Aug.8 (ANI): American intelligence officials believe that British forces have been defeated in Basra.

According to The Telegraph and the Washington Post, British commanders had reportedly allowed militias loyal to three Shia Muslim groups to take control of the city. ntelligence officials were quoted as saying that about 500 British troops based at the Basra Palace have been “surrounded like cowboys and Indians”.

Basra is one of four provinces handed over to British control after of the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. Three of the four provinces have been pacified and handed back to local leaders; Basra, the most populous, is due to be returned by the year end.

Both papers quoted Major Mike Shearer, a spokesman for the British command in Basra, as saying that the suggestion that UK troop levels in the province (5,500), had been cut too fast, was not true.

“This is not Dorset, but Basra’s crime levels are half the level of Washington,” he said.

A second British official in Basra, while admitting that violence has increased in the city, said the American criticism was misplaced.

Gordon Brown told George W Bush at their meeting at Camp David last week that British troops planned to hand over responsibility for Basra to local leaders within months, but that the decision was in the hands of British commanders.

Britain’s former governor of Basra, Sir Hilary Synnott, said the US criticism was payback for British claims two years ago that Basra was a success while Washington had failed in Baghdad.

A think-tank report has said the legacy of British rule in Basra was “the systematic misuse of official institutions, political assassinations, tribal vendettas, neighbourhood vigilantism and enforcement of social mores, together with the rise of criminal mafias”.

A spokesman for the British embassy in Washington said yesterday that the Washington Post report did not reflect America’s official position on British force levels.

Iditarod Trail 1925: The Serum Run (Conclusion)

The serum arrived, frozen, on Gunnar Kaasen’s sled at 5:00 a.m. February 2, 1925, two weeks after the first diphtheria death in Nome. Five people had died waiting for the serum to arrive. With 28 confirmed cases of diphtheria and as many as 80 people in Nome known to have been exposed, the 300,00 units of serum were gone long before the second shipment of 1.1million units arrived.

Dr. Welch later said that there were 70 confirmed cases of diphtheria in and around Nome that winter. Although the official death toll was five, Dr. Welch believed that the actual number was much higher since the Eskimo population may have buried children without reporting the illness. Without that first heroic run by 20 men and their hardy dogs, the death toll would have been much higher. And although the initial delivery of 300,000 units of diphtheria antitoxin serum is the one that made the headlines, without the same heroic effort made two weeks later by many of the same men and dogs, the casualties of the epidemic would have been much worse.

Ed Rohn, the man who had been sleeping at Port Safety when Gunnar Kaasen passed him by at 3:00 a.m. delivered the package containing 1.1 million units of serum February 15, 1925. Once again the teams braved howling winds and blizzard conditions to get the serum to Nome. The quarantine was lifted Saturday, February 21, 1925, a month after diphtheria killed little Billy Barnett and nearly three weeks after the first doses of serum arrived in Gunnar Kaasen’s sled.

The serum made it from Nulato to Nome in five and a half days, traveling along a mail route that normally took 25 days. Not only had the serum made it to nome in record time, it had done so in the dead of winter during a major winter storms in the Alaskan Interior as well as around Norton Sound.

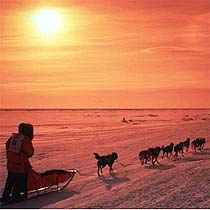

A Dog Sled Crossing Norton Sound

Wild Bill Shannon, the Irishman who was the first driver in the relay, returned from the initial serum run to Nenana with four dogs riding and five dogs pulling his sled. Three of the four riders, the same three he had left in Minto because of the pulmonary hemorrhaging, died a few days later. Shannon told a newspaper reporter, “What those dogs did on the run to Nome is above valuation. I claim no credit for it myself. The real heroes of that run …were the dogs of the teams that did the pulling, dogs … that gave their lives on an errand of mercy.”

His dogs weren’t the only ones sacrificed in the race to keep children alive at the top of the world in the dead of winter. Charlie Evans had borrowed two lead dogs for his run between Bishop Mountain and Nulato, both of whom died of frozen groins. Because dogs not specifically bred for the Arctic tend not to have thick fur in their groin area, mushers often wrapped the dogs in additional furs to prevent this problem. When Charlie Olson’s dogs began to suffer from frozen groins, he stopped and put blankets on each dog to keep them from freezing. Two of his dogs ended up badly groin-frozen. Ed Rohn’s lead dog, Star, was seriously injured in a fall into a fissure crossing Golovin Bay during the second serum run. Togo and one of his teammates didn’t make it back to Nome with the rest, either. They saw a reindeer and tore out of their harnesses to chase it, much like Henry Ivanoff’s dogs had done just outside Shaktoolik, about the time Leonhard Seppala happened by. Togo found his way home several days later, much to Seppala’s relief.

Leonhard Seppala and a Team of His Sled Dogs

Seppala always maintained that it was categorically unfair that Togo, the leader of the dog team which covered the most miles in the desperate race to save to the children, never got the recognition Balto received. Indeed, Togo is actually made a villain in Balto, that children’s movie I mentioned back in the first segment of this series. Should we blame producer Steven Spielberg and his ilk for making a truly exciting story intentionally wrong? Frankly, in this case, I do. The serum run is a story that is exciting and dramatic without having to resort to exaggeration, distortion of facts, or outright fabrication.

Leonhard Seppala

Togo and the man who drove his team, Leonhard Seppala, are names known mostly to hardcore followers of the Iditarod race. Seppala made the decision to cross frozen Norton Sound with the serum despite the danger of breaking pack ice that might have cost the team and the children of Nome their lives. Had he not crossed the frozen expanse of sea, though, more children would have died because of the delay in getting the serum to them. Seppala was already widely regarded as the territory’s best musher, and his part of the serum run was certainly the hardest of any of the 20 mushers who participated. Togo worked so hard on the Serum Run he injured himself and never raced again.

During the 625 miles the dogs and men ran from Anchorage to Nome, many Americans were transfixed by the story as it unfolded almost in real time in their homes via the marvelous invention called “radio.” The story gripped the imagination of the entire nation, and once the children of Nome were saved the team led by Balto began touring the country.

Within a couple of years, though, the dogs ended up a permanent attraction in one of the many vaudeville shows that were so popular at the time. The animals were apparently mistreated and not well cared for. George Kimball of Cleveland, Ohio, saw the team in Los Angeles and was appalled at their condition. With the help of Cleveland’s schoolchildren, $2,000.00 was raised and Balto and the rest of the team were purchased from the vaudeville show. The dogs lived in Cleveland for the rest of their lives. After Balto’s death in 1933 he was stuffed, mounted, and placed on display at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where I believe he is still a very popular attraction.

Balto, at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History

Togo is also preserved for posterity. His stuffed and mounted form is on display at the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race Gift Shop and Museum in Wasilla, Alaska.

Togo, at the Iditarod Trail Museum

The Seppala Siberian Huskies continue to be a much coveted bloodline. Leonhard Seppala imported his dogs from Siberia. They were dogs intended to work hard, pull loads, and last in the harsh Alaskan cold. Most of today’s Siberian Huskies tend to have characteristics more suited to racing, with shorter coats, longer legs, finer bones, and a narrower head. Seppala’s Huskies had wider heads with larger sinus cavities for warming the Arctic air; today’s Siberian Huskies need to be more concerned with heat than with cold.

The news reports of the Nome epidemic and the publicity afforded by the touring dogs inspired a drive to immunize children against diphtheria. The first successful diphtheria vaccine had been tested in 1924, less than a year before the Nome epidemic. Now, of course, diphtheria vaccines are part of all early childhood immunization programs. If there is any doubt as to whether it might be preferable to allow a child to have the disease rather than inoculate him against it, parents should read a description of the progression of the illness and be informed of the nearly 100% mortality rate prior to the discovery of the antitoxin serum.

In 1966-67 Dorothy Page and Joe Redington Sr. organized the first Iditarod Trail Dog Sled Race to commemorate the original serum relay. In 1973 the race was expanded to its present course. The entire course of the relay from Nenana to Nome has never been covered as quickly as it was between January 28 – February 2, 1925.

Resources for this series of blogs include:

Salisbury, Gay & Laney Salisbury, The Cruelest Miles: The Heroic Story of Dogs and Men in a Race Against an Epidemic (New York: Norton 2003)

Nome Convention & Visitors Bureau (http://www.nomealaska.org/vc/cam-page.htm)

The Official Site of the Iditarod (http://www.iditarod.com)

Kent A. Kantowski’s Serum Run Web Pages (http://www.angelfire.com/ak4/kakphoto/SerumRun/serum_run.htm)

Mike Coppock’s Serum Run Web Page (http://www.dountoothers.org/serumrun.html)

Race To Nome: The Story of the Iditarod Trail Dog Race (http://www.lucidcafe.com/library/iditarod.html)

Balto’s True Story (http://www.baltostruestory.net/)

Norman Vaughan Serum 1925 Run (http://www.serumrun.org/index.html)

The Seppala Siberian Sled Dog Project (http://www.seppalasleddogs.com)

Iditarod Trail, 1925: The Serum Run (Part VI)

Togo

Leonhard Seppala had gambled with the crossing of Norton Sound and won. He had crossed during the daylight hours of January 31, 1925, and although he could tell a storm was coming, it wasn’t there yet. The northeast wind was at his back as he left the roadhouse at Ungalik and pushed his fast toward Shaktoolik. Seppala had come 170 miles in his three days on the trail and believed he had about 100 miles to go before meeting the serum in Nulato. Togo and the rest of the dogs were making good time, had good energy, and so far had had good trail conditions.

A few minutes out of Shaktoolik Seppala saw another sled stopped ahead of him on the trail. The dogs had apparently started after a reindeer that had run across the trail and were tangled and fighting in their harnesses. Their driver saw Seppala and began waving frantically. Seppala had no intention of stopping to help. Time was of the essence. the wind was blowing at Seppala’s back and he wanted to take advantage of it as long as he could. As he passed the other sled, though, the driver jumped over the morass of agitated dogs and ran at him, screaming, “The serum! The serum! I have it here!”

The stunned Seppala had not gotten word of the change in the plans for the relay and had no idea that the serum could have made the trip from the railhead at Nenana in just three days time. Such speed was unheard of. It was true, though. The other driver, Henry Ivanoff, a Russian Eskimo who captained a ship on Norton sound in the summers, had taken the serum from Myles Gonangnan at Shaktoolik. He had been on the trail only a few minutes when he encountered Seppala. It was mid-afternoon, and the few daylight hours had turned to dusk.

Ivanoff informed Seppala that the epidemic had worsened and that the governor had ordered teams to run with the serum round the clock until it got to Nome. Worried at the news, Seppala wasted no time turning around and heading back toward Ungalik, 23 miles away. He was to take the serum back across Norton Sound if it was safe to do so, or run along the shore to Golovin, where Charlie Olsen waited to take the serum on the next leg of the relay. He was still unaware that his only child, eight year old Sigrid, was now one of Dr. Welch’s patients.

Having crossed the sound in daylight, Seppala knew that the coming storm would wreak havoc on the ice, and now that he was heading into the wind he realized that the storm was coming quickly.He had to cross the sound before the ice broke up or he and the serum, and Nome’s diphtheria victims, might all be lost.

Seppala and Togo had crossed the sound a number of times, but one time in particular had to be preying on Seppala’s mind as he headed toward it. Togo had been leading his sled across the sound during a northeastern gale on another occasion when, a few miles from shore, Seppala heard an ominous crack that let him know the sea ice was breaking up. Togo headed toward shore even before Seppala could give the command, but drew up short so fast he nearly flipped backwards. A yawning chasm of water had opened almost at Togo’s feet, but the dog had reacted quickly enough to avert immediate disaster. Seppala looked around and realized with dismay that he and his team were trapped on an ice floe and headed out to sea.

They spent more than twelve hours on that raft of ice, waiting as it drifted in the icy waters. Finally it neared land, but ran up against another floe that was jammed against the ice still connected to shore. they stopped moving, but there was still a five foot gap of water that Seppala couldn’t hope to cross. He tied a lead onto Togo and heaved the dog across the water. Togo landed on the ice and sensing what Seppala intended, the dog began pulling with all his might, narrowing the gap between the two ice floes. Then the lead rope snapped. Seppala thought he was a dead man. Then Togo, showing himself to be possessed of more intelligence and resourcefulness than most men could expect from even their lead dogs, leaped into the water and grabbed the broken end of the lead rope in his jaws. He clambered back onto the ice and continued pulling until he had narrowed the gap enough for Seppala and the sled to cross safely.

Seppala knew that he would be trusting Togo completely to make a night crossing of Norton Sound in another northeastern gale. In the Arctic darkness, and in a blowing blizzard, Seppala wouldn’t be able to see to color of the ice or hear it creaking. He didn’t hesitate, though. When he reached the Ungalik he put his life, and the lives of Nome’s diphtheria patients, in Togo’s capable paws.

His trust was not misplaced. At 8:00 that evening, Seppala and Togo pulled back onto shore at Isaac’s Point. They had crossed Norton Sound twice in one day, traveling a total of 84 miles. Such a distance was incredible. They would rest at the roadhouse at Isaac’s Point until 1:00 a.m., then head out again. The next driver of the relay was waiting at Glolvin, another 50 miles away. As the dogs and the man slept, the ice in Norton Sound began cracking.

By the time Seppala hitched Togo and the rest of the dogs to the sled again, the wind was howling. An old Eskimo man warned Seppala not to go back out onto the ice of the sound, and Seppala would heed the advice for the most part. But unless he drove across the ice, the trail between Isaac’s Point and Golovin was extremely rugged. In fact, the current path of the Iditarod Race follows a different trail because of the dangers. Seppala’s route from Shaktoolik to Golovin was made even worse by high winds and temperatures of less than -40 degrees.

The ice Seppala and Togo had crossed just hours before had already begun to break up, so they also faced the constant threat of the ice breaking apart beneath them, even just a few yards from shore, and yawning chasms of open water. The howling wind blinded Seppala and, again in the darkness, he trusted Togo entirely. Once they crossed the last bit of frozen sound, Seppala had to be relieved, especially when he learned that by the time the sun rose the entire expanse where they had driven broke up completely.

Despite the potential hazards of the open ice, the most grueling portion of Seppala’s leg of the relay was about to begin. The team would have to climb eight miles along a series of ridges, including the 1,200 foot summit of a mountain called Little McKinley. Seppala’s hardy team was exhausted, but never stopped. They reached Little McKinley’s peak then descended three miles to the Golovin roadhouse, arriving thirteen hours after they had set out from Isaac’s point with only five hours of rest. Seppala and Togo and brought the serum 135 miles, and now, with the northeastern gale threatening even more, the serum was 78 miles from Nome and the dying children.

Charlie Olson took the Serum from Golovin to Bluff, where Seppala’s colleague, Gunnar Kaasen, was waiting with another team from Seppala’s kennels. Kaasen was to take the serum from Bluff to Port Safety after stopping to warm the serum at the Solomon Roadhouse. From Bluff, Ed Rohn was to take the serum into Nome.

None of these drivers knew how bad the storm was, though. Back in Nome, Dr. Welch was in worried conference with the public health officials. The mushers were carrying enough serum to treat 30 people, and 28 were already in Dr. Welch’s hospital. If the storm worsened and the serum was lost or frozen, all of those people would probably die. With the worsening storm threatening more than just the men on the trial, the decision was made to halt the relay until the storm had passed. Nome’s mayor could only guess where the serum was at this point, but it was almost a moot point since the telephone line only reached as far as Solomon. The mayor called the roadhouse at Solomon, where Kaasen was to rest and warm the serum, and gave the order that Kaasen should stop there until the storm passed. Word was also sent to Ed Rohn who was waiting at Port Safety, just 21 miles from Nome.

Kaasen hadn’t yet gotten the serum when the call went out, though. Charlie Olson had been hit with hurricane force winds on his leg of the relay and was making very slow time. At one point he was blown into a drift and had to dig his way out with his bare hands and then free the dogs. The fight against the wind and the blowing snow had exhausted him and he had not been able to warm himself up after digging out of the snow. When he arrived at the roadhouse at Bluff, Olson’s hands were so stiff with the cold that he couldn’t get the serum off the sled by himself. His dogs were nearly frozen, too. Their vulnerable groins were stiff with the ice and cold and the dogs limped into the roadhouse to get warm themselves. As they waited for the serum to thaw, Olson pleaded with Kaasen to wait for the storm to pass before heading out.

Kaasen was reluctant to wait. He had put together a team from Leonhard Seppala’s kennels, and believed that with the steady, strong Balto in the lead position he could make it. Balto was inexperienced as a lead dog on a run like this, and Seppala had left instructions that if another team needed to be put together his choice for the lead was a dog named Fox. Kaasen preferred Balto, though. He waited with Olson for a couple of hours. The storm showed no sign of abating. Kaasen went out at one point wearing sealskin mukluks, sealskin pants, a reindeer parka, and a second parks over that one. The wind pierced the furs, but Kaasen decided to head out anyway. He was afraid that if he waited the trail to Solomon and Port Safety would be blocked by drifts.

Just five miles from the Bluff roadhouse, Kaasen met his first drift. Balto tried to go though it but got mired in the snow. Kaassen couldn’t punch through the drift, either. Balto would have to find a way around. The dog was on an unfamiliar trail in the dark of night during a raging blizzard. He put his nose to the ground, though, and within a few minutes the team was running down the trail toward Solomon. A few miles further on the trail followed the frozen surface of the Topkok River. Kaasen was startled when Balto suddenly stopped and refused to go again. He realized that the dog had stepped into the water of a spot of overflow. Kaasen steered the team off the river and dried Balto’s paws, then ran them along the ridges toward Topkok mountain.

The storm was so bad by this point that Kaasen had no choice but to trust Balto to find his way along the trail. The man just held onto the sled and let the dogs do the work. It wasn’t until he recognized Bonanza Slough that he realized that he had completely missed the Solomon Roadhouse in the dark and the blowing snow. He was at least two miles past it. Rather than turn back, though, Kaasen decided to keep pushing toward Port Safety and the next leg of the relay. Because he missed the roadhouse, he never got the message that the health officials had ordered the relay halted to let the storm pass.

He started the dogs back on the trail through Bonanza Slough. The slough created a wind tunnel for the hurricane force winds of the storm. More than once the sled was literally picked up by the wind and the dogs became tangled in their harnesses. Each time Kaasen had to remove his gloves to right the sled and untangle the dogs. Then a particularly mighty gust picked up the team and tossed them all into a drift. Kaasen had to dig himself and the dogs out. He felt the bed of the sled for the serum. The box was gone! Panicked, Kaasen floundered around in the drift, finally locating it. He lashed it to the sled with extra straps this time and without further incident made it to Port Safety.

Believing that Kaasen would stay at Solomon, Ed Rohn had gone to bed at the Port Safety roadhouse. Kaasen considered waking him, but rejected the idea since Rohn’s dogs would have to be fed and then hitched to the sled for the continuing trip. It was about 3:00 in the morning, and Nome was about 20 miles away. Since leaving Bonanza Slough the storm appeared to be abating somewhat, so Kaasen decided to press on.

At 5:30 a.m. Gunnar Kaasen pulled into Nome with the serum. “Witnesses … said they saw Kaasen stagger off the sled and stumble up to Balto, where he collapsed, muttering: “Damn fine dog.”

Leonhard Seppala with Togo, and Gunnar Kaasen with Balto

Next: the Conclusion

Iditarod Trail, 1925: The Serum Run (Part V)

Half an hour after Charlie Evans and his dead lead dogs had arrived in Nulato, the serum was thawed and Tommy Patsy, another Athabaskan driver with a formidable reputation for his wilderness survival skills, headed down the trail following the Yukon River to Kaltag, the last stop on the run before the trail rose into the Nulato Hills. He covered his 36 miles in about three and a half hours, making the best time of the entire relay at just over 10 miles per hour.

Jackscrew, a Koyukuk Indian, took the serum through the mountains from Kaltag to Old Woman Shelter. To lighten the dogs’ load and make better time on this difficult stretch of the trail, Jackscrew ran uphill through the woods of the Nulato Hills for a good bit of the first 15 miles of his 40 mile leg of the relay. Once he passed the Kaltag Divide and headed downhill toward Norton Sound, he climbed back aboard the sled.

Victor Anagick took the 34-mile leg from Old Woman Shelter to Unalakleet, across mostly open tundra and through the stunted coniferous taiga closer to the coast, where he passed the package to Myles Gonangnan, an Eskimo musher.

On the morning of Saturday, January 31, at Unalakleet on the southern shore of Norton Sound, Gonangnan took the measure of Norton Sound. He had to make the decision as to whether to cross it or go around it. The shortest route from Unalakleet would have been straight across Norton Sound to Nome. Leonhard Seppala had been warned against taking this route as it was entirely too risky. The center of the sound at this point rarely froze entirely because of the currents and motion of the water.

Norton Sound is an inlet of the Bering Sea. Nome, Alaska, sits on its north shore. The sound is about 150 miles long and about 125 miles across. Norton Bay is its northeast arm. The Yukon River, along which the teams of dogs drew their sleds carrying the precious diphtheria antitoxin serum in January 1925, flows into the sound from the south. The sound is only navigable from May to October. In October the sound begins to freeze as average temperatures dip well below freezing. By January, when the average temperature is below zero, the sound is completely frozen.

The closer you got to the sound, the more conscious you became that the ice was in a constant state of change and re-creation. huge swaths would suddenly break free and drift out to sea or a long narrow lead of water would open up…. Depending on the temperature, wind, and currents, the ice could assume various configurations – five-foot-high ice hummocks, a stretch of glare ice, or a continuous line of pressure ridges, which look like a chain of mountains across the sound. …

Then there was the wind. It was a given on Norton Sound that the wind howled and that life along these shores would be a constant struggle against a force that tried to beat you back at every step of every task. But when the wind blew out of the east, people took special note. These winds were shaped into powerful tunnels, and gusts barreled down mountain slopes and through river valleys, spilling out onto the sound at spectacular speeds of more than 70 miles per hour. The could flip sleds, hurl a driver off the runners, and drag the wind chill down to minus 100 degrees. Even more terrifying, when the east winds blew, the ice growing out from shore often broke free and was sent out to sea in large floes.

—The Cruelest Miles, pp. 195-196

The overland route was safer than crossing the sound even in the best conditions. Gonangnan considered the fact that the wind had been blowing for several days from the west, pushing the ice against the coast and raising the level of the ice in the sound and weakening it. Had the wind remained from the west, the decision would have been easier. Even if the ice broke into floes, it would be blown toward shore and a sled team could navigate safely along the floes to shore. With the shift in the wind’s direction, though, the ice was being blown out to sea. More disturbing was that the northeast wind was building in strength. A storm was coming and would be there soon. When it came, the ice would be likely to break up. He decided not to risk the shortcut directly across Norton Sound. He turned northeast, toward Shaktoolik.

On the other side of Norton Sound, at about the same time, Leonhard Seppala was facing south and facing the same decision as Myles Gonangnan. Although he had been told not to risk the crossing, he knew that the fastest way to get the serum in the hands of Dr. Welch was to go across that frozen expanse. In two days he had covered about 110 miles, and had 200 more to go before he got to Nulato where he believed the serum would be waiting. Word had not reached him that not only had the number of teams in the relay increased tenfold, but that the serum had passed Nulato 24 hours before and was just on the other side of the sound.

Seppala decided the time saved by crossing the sound was worth the risk. Doubtless he would have hesitated even less had he known that his own daughter, Seigrid, had been admitted to Dr. Welch’s infirmary that very morning with diphtheria. Five more children had died, and twenty-seven were in the hospital, and at least eighty were known to have been exposed. Nome’s epidemic was in full swing. What was worse, one of the diphtheria patients was the daughter of the owner of a roadhouse at Solomon, a small settlement near Nome. The girl had been helping to cook for guests at the roadhouse. The grim fear was that she may have unwittingly spread the disease beyond Nome.

Later that day, Dr. Welch was told that Myles Gonangnan had left Unalakleet. With great relief Welch sent a telegram to the Public Health Service saying that the 300,000 units of serum from Anchorage was expected by noon the following day, February 1. Dr. Welch was unaware that the weather was conspiring against his patients.

The trail between Unalakleet and Shaktoolik is windy even in good weather, but sometimes the winds can blow from the north at more than hurricane force, with temperatures well below zero and chill factors worse than minus one hundred. Winds like that create ground blizzards, white-out conditions in which a sled can flip and men and dogs can freeze trying to find each other.

As the wind rose on the souther side of Norton Sound, snow blew in deeper and deeper drifts. At last Gonangnan had to break trail for his dogs. Breaking trail consisted of walking back and forth across the trail in snowshoes, tamping down the snow until it was firm enough to hold the weight of the dogs. The trail breaking was a slow, laborious effort. In five hours, Gonangnan had made only 12 miles. He stopped at a fishing camp to warm himself and the serum. He knew he was still at least nine hours from Shaktoolik, and had extremely difficult terrain to cross.

Five miles further along the trail were the Blueberry Hills, where the team would have to climb a 1000 foot summit then descend again to the beach. Wind tunnels in this region were brutal enough without the addition of the storm Gonangnan knew was coming. From the fishing village to Shaktoolik there were no shelters, abandoned or otherwise. If the storm hit while he was on this stretch of trail, it would be unpleasant indeed.

The wind was vicious and unrelenting on the way up the Blueberry Hills. By the time the team reached the summit Gonangnan was blinded by whiteout conditions. He had no time to prepare when the team suddenly began its steep descent toward the dunes along the sound. He held on and held his breath for the next three miles, and made it safely down to the beach only to find that the wind was blowing at gale force and and the wind chill was at least -70 degrees. He rode the sled for another four hours, arriving at Shaktoolik at 3:00 p.m.

There was no sign of Leonhard Seppala. Where was the famous musher?

Next: Seppala, Togo, and Balto

Iditarod Trail, 1925: The Serum Run (Part IV)

Newspapers had picked up the story of the epidemic early. As the tone of the telegrams between Nome and the outside world became more urgent, radio began to carry the story to an even broader audience. Winter storms swept across the continent as Nome waited for the serum, and people enduring zero degree weather on the East Coast were amazed at the determination and hardiness of the dog sleds driving through temperatures more than 50 degrees colder. The entire nation was transfixed by its radios, chewing its fingernails in hopes that the men and dogs could brave the blizzards and hurricane force winds of the Alaskan winter storms, cross an untrustworthy seasonal ice pack, and deliver the serum to the exhausted doctor and nurses as the number of victims reportedly rose with each passing hour.

On January 28, the exhausted and frostbitten Wild Bill Shannon handed the package over to a 20 year old Athabaskan musher named Edgar Kallands at Tolovana. Kallands made his five hour, 31 mile run to Manley Hot Springs under essentially the same conditions that had nearly done Shannon in. The temperature was -56 Farhenheit. When Kallands arrived in Manley Hot Springs, his gloves, with his hands inside, had frozen to the handlebar of the sled. “The roadhouse owner had to pour boiling water over the birchwood bar to pry him loose,” the Associated Press reported.

At Manley Hot Springs, the precious cargo was handed to Dan Green, who took it another 28 miles to Fish Lake, where another Athabaskan driver, Johnny Folger, took possession of it and got it to Tanana, another 26 miles closer to Nome. At each stop, just as the Anchorage doctor had instructed, the serum was warmed for fifteen minutes. From Tanana, Sam Joseph, also an Athabaskan Indian, took the serum another 34 miles to Kallands, the settlement named for the family of young Edgar Kallands. Titus Nikolai then transported the package 24 miles to Nine Mile Cabin, where he gave it to Dave Corning. Corning took it another 30 miles to Kokrines, then Harry Pitka took it the next 30 miles to Ruby. At Ruby, Bill McCarty took over and drove 28 miles to Whiskey Creek, where Edgar Nollner waited. Nollner delivered the package to his brother George at Galena, another 24 miles closer to Nome.

George Nollner took the serum 18 miles to Bishop Mountain. He arrived at 3:00 a.m. on Friday, January 30. He and his friend Charlie Evans, the next driver in the relay, sat in the relative warmth of the cabin. Like everyone else along the way, they were worried that the deep cold and the infrequent thawing of the serum would render it useless. The temperature at Bishop Mountain was -62 degrees Fahrenheit, and Evans had thirty miles to go to Nulato, the halfway point, where Leonhard Seppala expected to take possession of the precious serum and return to Nome.

Evans ran into trouble as he approached the convergence of the Koyukuk and Yukon rivers. Water had broken through the ice and the trail was covered with dangerous overflow. Overflow is caused when because of the pressure beneath the solid surface of ice, water breaks through in a gush, then continues seeping. Sheets of extremely slick, glacier-like ice result from the water flowing over the ice. An ice fog also develops at about -50, when the relatively warmer water vapor from the overflow turns to tiny ice crystals in the air. The ice fog Evans encountered was as high as his waist. He could no longer even see his dogs, much less the trail.

Eventually, a breeze began to blow that dissipated some of the ice fog. This was a mixed blessing, though, because with the breeze came a worse wind chill. Evans couldn’t get off the sled to warm himself with exercise. If he did, and the ice fog thickened again, he’d be lost, and the dogs would have gone on without him. Less than ten miles from Nulato, the unthinkable happened. Evans had two lead dogs he had borrowed for the run. First one collapsed and had to be loaded onto the sled, then the other collapsed. Evans hitched himself to the sled and led the team the rest of the way to Nulato. When he arrived about 10:00 a.m., both lead dogs were dead.

The serum had arrived at the halfway point in three days, the shortest time that distance had ever been traveled. Leonhard Seppala had expected to meet the serum in Nulato, but the Territorial governor had other ideas. On that Friday, January 30, ten days after Dr. Welch had confirmed diphtheria among Nome’s population, the death toll stood at five. Getting the serum to Nome as fast as possible was paramount.

Leonhard Seppala, who held the records for the fastest runs by dog sled, had set out from Nome on January 26 planning to travel a total of 630 miles. Traveling that distance without rest would be impossible and time was of the essence. Alaska’s territorial governor made the decision to add more drivers and dogs to the number making the relay. The idea was that the fresher the teams were, the faster they’d get the serum to Nome. All in all 20 drivers and their teams of dogs would be participating in the relay.

Seppala had already set out on the first 315 mile leg of his journey, though, and he was still the best one to take the serum across the pack ice of Norton Sound. Driving across the frozen sound would shave a full day off the time it would take to get the serum to Nome. There was no way to get word to Seppala, though, that the plan had changed. As drivers were called to participate in the relay they were told to keep a look out for Seppala and to hand the serum over to him when they saw him.

Next: Crossing the open ice of Norton Sound; and the canine heroes Togo and Balto